On our drive from school the other day my tweenage son told me a classmate had offered him a joint. I’d been preparing for this moment, staging it in my head for years, ready with my bag full of allegorical stories of my reckless youth before easing into the “Why drugs are bad for you” speech. But as I drove home searching for how to begin, I remembered when I was a teen, walking in on my sister’s confession, and my twisted interpretation of her troubling story…

I was fourteen, finishing 8th grade. Another sunny day in L.A., and I came into my house sweating from my twenty-minute walk home from middle school. I heard my sister talking in our parent’s bedroom, which was usually off-limits to anyone but them. When I got to their doorway, I saw my sister and mom sitting next to each other on the end of our parent’s bed. They stared at me standing in the threshold, looking more like siblings the way their short, thick dark hair framed their tear-streaked faces.

I migrated into the room looking back and forth between them and asked what was going on. They shared a non-verbal exchange as I sat across from them on the little cushioned chair in front of the mirrored vanity. After some time trying to gain her composure, Mom finally launched into the reveal. She wiped away her tears, then told me that my sister had been ill. This was not hard for me to fathom, since in the last year she’d dropped a lot of weight, and more recently, her skin was turning orange.

We were not close siblings. She was two years older and had worn her weight loss like a badge of honor, but with my mom’s assertion I felt the ground falling away thinking of cancer or some other horrible life-threatening illness. My mother continued to explain that my sister had been starving herself for the last few years to lose weight, and had started vomiting most of what she did eat this past year to stay thin. She became so overwhelmed with grief in the telling that fresh tears slid down her cheeks. She covered her mouth and sobbed.

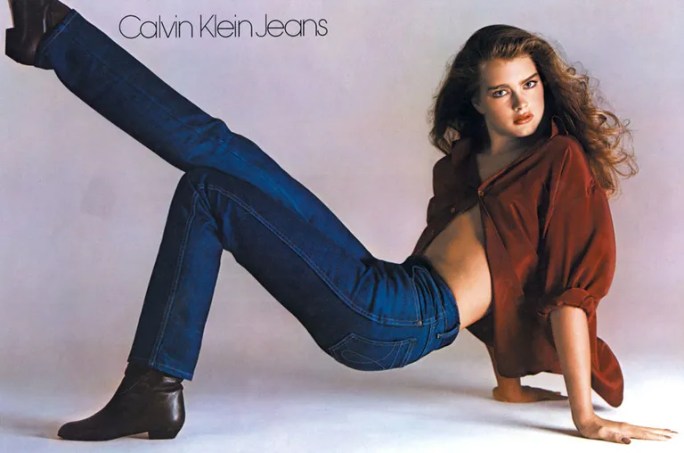

My sister took over, delivering her words vacillating between shame and pride. She sat perched on the edge of the bed and confessed to years of fasting and purging because skinny was in, and she didn’t want to be left out. She touched on her orange skin from eating lettuce and carrots exclusively for days. She talked about losing her period, her reason for confessing to our mother, afraid she’d become sterile. Then she changed tracks, and clearly delighted, she spoke of shopping with friends, and finally fitting into the skin-tight Calvin Klein jeans that the actress Brook Shields famously posed in. My sister had become part of the in-crowd and reveled in being desired by the popular boys in school. Like most of her high-school girlfriends, she’d finally achieved what I thought impossible for our well-endowed family lineage. She was unarguably thin.

My mother had regained her composure and sat next to my sister silently ringing her hands. I sat on the little cushioned stool staring at my skinny sister, consumed with jealousy. I wanted to be her. I, too, wanted to be rail thin, heroin chic, a cover-girl stunner like my big sister. To me, she was beautiful — sleek, tight, hip, slick and trendy. She was what I too aspired to be, what every magazine, TV show, and movie showed attractive, desired women should be. Thin.

And she’d just told me how to get there.

What I heard her say that afternoon was starving and vomiting worked to lose weight. I failed to acknowledge her detailed account of the toll the eating disorder took on her body and mind. I stopped listening right after she told me how she’d gotten skinny. Everything that followed was white noise.

From that day forward, and for the next five years I threw up frequently after eating to purge my body of the calories. I starved myself for days, sometimes going for weeks eating just vegetables. I tried to ignore that I was tired all the time, and chronically cranky, and falling into a black kind of depression. The desire to be thin superseded all reason. If my sister could do it, I could, and would, and did, regardless of the health risks.

Several years in therapy with a nutritionist gave my sister the fortitude to eat healthy, combat social pressures and become more accepting of her body. I learned to control my weight with exercise. Racquetball and running eventually replaced retching, but every time I over-indulge I consider throwing up to rid my body of the unwanted calories. To this day my sister’s words still echo in my head and taunt me — not all of what she said, only what I heard.

I pulled my Prius into the garage this afternoon and I looked at my beautiful son in the rearview mirror awaiting my lecture. My stomach hurt from the pasta salad I’d eaten for lunch earlier. My heart hurt — lost for words of wisdom for my kid. I wanted to purge my body of the heaviness, then shook my head in disgust at the notion, hoping my son didn’t catch it. Thirty years later, I’m still fighting the voices inside my head that rationalized my sister’s eating disorder as a workable solution to weight loss.

I led my son into the house for a snack and a chat. And I lied. I made up a tale of a friend’s reckless behavior that led to disaster. I told story after story of kids I went to high school with who were users and grew up to be losers (though I knew none). I assured him popularity did not come with using. I left no space for him to surmise drugs were simple fun, or required to be ‘in.’ I chose my words carefully, considered them from many angles for possible distortion before speaking, even asked him to summarize what I’d said often to make sure we were on the same page. And though he parroted my sentiments in detail, in recalling my experience with my sister, I am left with lingering concern he didn’t really hear me.

Sometimes, between what is said and what is heard is the Grand f***ing Canyon.