My 21-year-old daughter decided to give me an assessment of my parenting of both her and her brother on her visit home from college at the end of summer break. Among my many crimes, I was cheap, though my college senior has never paid a bill in her life, not for her education since we float those bills, not her phone, not her car, which I gave her mine when she needed one, not even car insurance. Every birthday she received piles of presents that she actually wanted, (not clothes, like my mom gave me), usually well over a grand. And let me be clear, we are squarely middle-class, and at times throughout their formative years, we struggled to make the bills.

Spoiled brat? Maybe. But both my husband and I felt our kids should focus on academics and socialization, and use their meager part-time job earnings for fun. Adulting would come after college, along with the pressure of earning enough to pay their bills.

We sat at Caliente’s eating chips and waiting for our meals as she continued to list my failures. I gave unsolicited advice when we spoke, and she just wanted to rant. I tell people when and why I’m disappointed in their behavior, like customer service reps who show no desire to help, but no one cares what you have to say, Mother. I was violent sometimes when I got angry.

Did I ever hit you, or even spank you? Throw anything at you? I asked her, trying to be patient, listen carefully and address her complaints.

No, of course not.

Have you ever been afraid I’ll strike you? Or hurt you physically, ever?

No. I know you’ll never hit me, or throw anything at me, or hurt me like that. But when you yell, or cuss, or throw your napkin down on your plate when you’re angry, it’s really aggressive, so those times you’ve been emotionally violent. My daughter is on the medical track, to become a doctor, with a minor in psychology.

Wow. I’m sorry I made you feel that way. Do you feel like I’m aggressive a lot? She was completely undermining my self-image. One of my best bits is I am non-violent in the extreme. I’ve preached to both my kids that violence is unacceptable other than in self-defense when in imminent danger.

No. Most of the time you’re pretty chill, except when you and Dad are at it, then you trigger quicker.

We went round about over aggressive vs violent, then she finally moved on to the coup de grace.

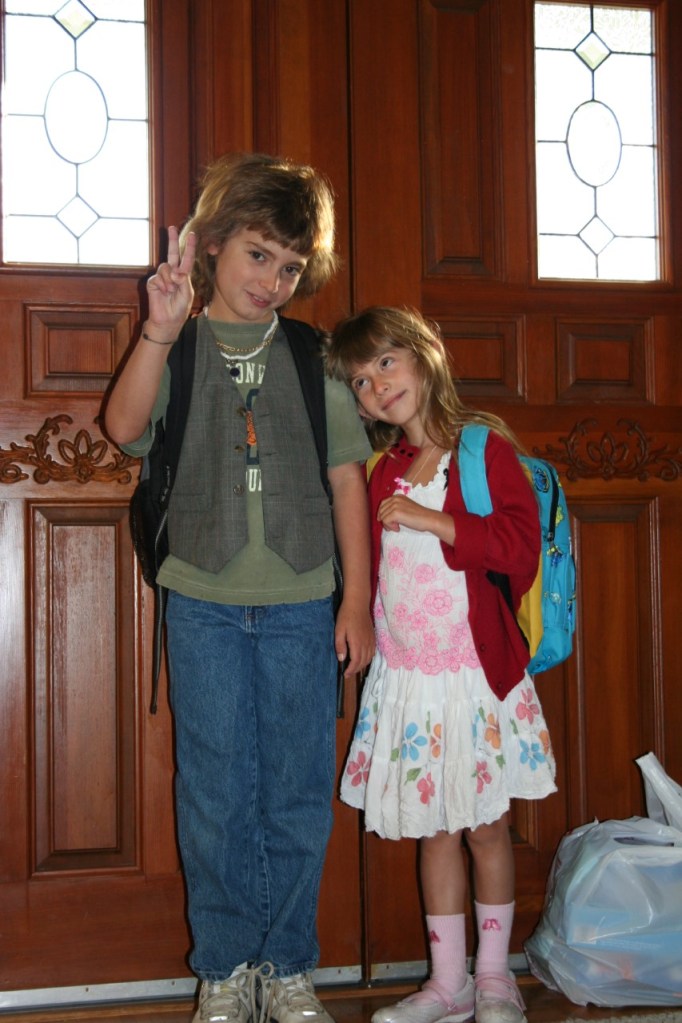

You raised your son like a girl, she said as the waiter put our meals in front of us, then retreated. You did, Mom. You taught him to share his feelings, and he does. Too much, for a guy. You made sure to point out sexism in social norms, movies, in politics, and business, and how often men think with their ‘little head.’ You raised your son to think like a woman, and it hasn’t helped him any.

I sat there chewing my first [and last] bite of the three Street Tacos on my plate. I chewed until it was basically mush in my mouth to swallow it because my throat had constricted with my daughter’s harsh critique. To her point, our son battles depression and has since his first year in middle school. But until my daughter called me out right then, I hadn’t considered raising him to be empathetic, more aware of his own feelings and how he affects the world around him as a ‘girl’ thing.

I raised you both the same, I told her, fighting the tears now welling in my eyes.

I know, she said with the confidence of a professor. That’s the problem. Beyond logistics, most boys don’t learn to communicate. They’re taught to compete, which is why boys make friends through sports.

We enrolled your brother in baseball, soccer, Boy Scouts, taekwondo—

Yeah. But he liked talking to his teammates more than playing the game. You made his life totally harder because he doesn’t fit into his gender. And he’s not gay. So, you really screwed him up —

I’m done, I said. You’ve spent the entire day beating me up. And I’m done. I threw my napkin on my plate. Oh, shit, that was aggressive, I said to my daughter, then got up, paid the lunch bill, and came back to where she still sat, staring down at her Carne Asada. I could not stop the tears from streaming down my face when I told her to take the car, and that I’d walk to get mine at the shop, but I didn’t want to be with her anymore right then. Then I walked away. I’d never, ever, walked away from either of my children.

I got maybe 100 yards, out of the mainstream and melted down, sank to my knees against a shop wall. It took me a good five minutes to stop hysterically crying before I was able to walk to the repair place and deal with the mechanic. I got my car and drove out to the lake, walked to the end of the pier and sat on the bench, sucking in the wet air to catch my breath, and reasonably, calmly, assess my daughter’s many assertions.

I’m cheap. Hmm, she didn’t use the word ‘cheap.’ She said, you’ve been tight with money. Too tight. A politically correct way to say ‘cheap.’ Since my daughter doesn’t have a clue about the cost of even her current lifestyle, I discounted her assertion I was cheap with her lack of actual knowledge.

I was violent. As I explained to my daughter over our brief lunch, the word ‘violent’ means “using physical force intended to hurt, damage, or kill someone or something,” a la Google, as I asked her to look it up over chips and salsa. I abhor violence. Growing up, my 6’3”, 230-pound dad used to hit me when he encountered my resistance. My father was violent. I’ll cop to being aggressive when I’m angry. Maybe too aggressive, and I will work on backing that off.

I took a deep breath and let it out slowly, a first step towards calm over anger, reason over rage.

I raised my son like a girl because I taught him the same lessons that I taught to my daughter…

I sat on that bench staring out at the lake until almost sunset thinking about her assertion. I realized I was shaking, I assumed from the chilly night approaching, until I got in my car and turned on the heater but didn’t stop. I was trembling with outrage.

I got home half an hour later. My daughter was in her room, very upset, my son assured me, though he didn’t know exactly why. She’d only told him we’d had a fight and I left. I went to her room and asked her to meet me in my office, a private space a quarter acre from the house, so we could talk. She came in a bit after me.

I love you, I began when we were seated. I love you, I repeated, locking my eyes on hers hoping to transfer the intensity of love I feel for her. I want the best for you, and for you to be the best of you.

I love you too, she said. And I’m so sorry for this afternoon. You are my best friend, and I’m sorry I hurt you.

I get it. Me too, for leaving. I’m sorry that hurt you. I needed space to think about all the stuff you said to me. I’m ready to talk to you about that now. And I may get aggressive because I am so hurt by so much of what you said, but I won’t ever be violent. I smiled to ease the tension.

She did too. I know, she conceded. I’m sorry I said that. I know it’s not true.

OK. Thanks. I took a breath but kept my eyes on hers. First, when you start paying for your education, your car, your insurance, your phone, and all your other expenses that we pay for, only then will you have the knowledge to assess if I am cheap.

I didn’t say you were cheap, Mom —

Yeah. Ya did. And I’m not going to sit here playing word games with you. You know what I mean. I felt my heart racing. A typical passive/aggressive play my husband, her father, engages in when we’re in conflict is grammar-nazi, nitpicking every word I use to derail the dialog.

I’m sorry, Mom. I know how hard you’ve worked to make sure we got taken care of through college. I’m really sorry I said that. And she started crying.

And so did I, seeing her hurt, and knowing I still had a hard lesson to teach. My talented, beautiful daughter, I began. I love you, I repeated, to remind myself how much I did amid the outrage I felt towards her right then. You accused me of raising my son like a girl. And out of all the things you said to me today, this cuts the deepest. Have you said this to your brother — that I raised him like a girl?

She looked down, said No, but I didn’t believe her. Then she looked at me and said, I don’t remember saying it to him. I don’t think I did, anyway…

If you’ve told your brother I raised him like a girl, you’ve diminished the best of him. The best of any human — man or woman. He is kind. Truly kind, not just words but actions, volunteering at the food bank, and working in nonprofit. Your brother is compassionate. He really cares about how people feel, knows how to listen, and empathize. He examines his feelings and has the grace, and humility to look for and admit his culpability, and then take responsibility for his screw-ups. And I get your brother may have a harder life being different from most men his age. But I refused to raise my son as most boys are still raised — to reflect their father’s bravado from our caveman days.

I felt my heart race and heard myself getting louder and faster with my delivery. I stopped speaking and took a deep breath. My daughter sat in my high-backed leather office chair, her hands clasped in her lap, looking rather small, way younger than her almost 22 years.

I love you, I repeated, to give her ground.

I love you too, my daughter said, tears streaming down her face.

You’ve admitted I raised both of you the same. And I meant to. I worked hard to treat you equally, and respect you both as individuals. I gave you the same messaging, not as male or female, but as people. I raised you both not to reflect your dad and I, but to be better than us — smarter, more connected inside yourself, and more responsive to the world you touch. Not boy/girl, or sexist norms passed through generations, but to meet our compassionate, creative potential regardless of gender — be the best of what we are. I fixed my eyes on my daughter’s, trying to impart to her what I know to be true.

Children can stop racism, when they are taught to understand instead of hate.

Children can stop sexism, when parents teach their kids that their value lies in their actions, not their gender.

Children can stop the greedy few from controlling the many by implementing laws for an equitable society, and sustainable stewardship of this planet.

Tears now streaming down both our faces, I stared at my daughter.

No pressure there, she said with a half-smile.

I smiled too. Between theory and the need to change the direction of our current reality is the grand fucking canyon. An audible sigh escaped me. Sorry, kid. You were born owing the gen before you to contribute to the living and the lives that follow yours. It comes with the privilege of being Human.

I get it, Mom. And I said things I didn’t mean today. And I’m sorry.

I know. Me too. For all the times I’ve failed you, I’m so sorry. I get you’re mad at me for something, but I’m thinking it ain’t most of what you said today. So, let’s explore what you’re feeling, and drill down on what you’re really upset about…