I’m a ‘sit on the couch and eat ice cream’ type of person. I don’t live that way. I workout 5 days a week, 5 miles or more a day, watch little TV and rarely stream ’cept when I’m working out and weekend movies. If I had no desire to live an active life, I would have continued to sit on the couch in front of the TV and eat a lot more than just ice cream as I did throughout much of my childhood.

Thing is, no matter how healthy I live, I’m still going to die. And while we all know this fact, generally by the time we are 5 yrs old, we don’t think about it much unless there is a life-threatening scare or we’re facing old age, like when we turn 60 or so. Then, regardless of what older folks tell you, and how we distract ourselves with work or hobbies or relationships, we think about death a LOT.

Am I living right? Getting the most out of this short life? Have I experienced enough? Have I loved enough? Have I had enough fun? What can I do to get the most out of the few years I have left?

What to do with aging…

The idea of heaven is vulgar. I think The Good Place played that hand well. At the end of the series, they were all up in heaven and got so bored after doing everything they could conceive they elected to become nothing, or ‘one with everything’ depending on how you view the afterlife. And ‘getting to see’ people you’ve loved in the hereafter is equally vulgar. Sure, you’ve loved them, but I bet you’ve fought with them too. Can you imagine spending eternity — forever — with your mom and dad and siblings and spouses? No thank you!

I am a devout Atheist, meaning I don’t believe in god, or even the possibility of one. I don’t believe in an afterlife, or spirituality, whatever that means. Hitler (Trump) and I end up the same. Dead is dead. End of game. Life is over and there is no ME anymore. I did not exist before my birth and I cease to exist after I die.

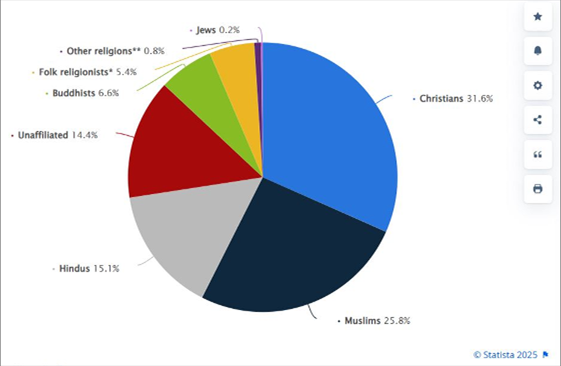

It’s easier to believe in the Christian version of death. Less scary thinking your existence is eternal. That’s why, to date, 31+% of this planet identifies as Christian. Muslims, the second largest religion on Earth, also offers an afterlife in paradise or hell. Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism also preach forms of life after death, so it’s no wonder that 84% of humanity identifies with a religion.

The roughly 14+% of the rest of us living day-to-day knowing that we all become nothing after death is core scary at best.

We all want to feel our lives have significance. Substance. Meaning. That we matter! It is why social media exists — it plays on our desire to be seen. Every time we get a Like on our instastory, or see a high view or engagement count we all get a hit of dopamine straight into our brains. We may be shy, or awkward in groups or crowds, but no one wants to be invisible through life. We revel in being seen.

Now, facing old age, and likely 20 to 30 yrs on the outside before ceasing to exist, I’m at war with myself daily on how to spend the limited time I have to live, to BE ALIVE. To matter.

What does it really mean to MATTER? Three generation drops from now and most won’t remember today’s trending influencers, to our current or past pop/rockstars, to our great grandfathers. I know this intellectually, but emotionally I too want to be remembered by more than just my remaining family, and when they go, so does my memory, my significance. It’s hard, if not impossible to imagine not existing, though at 4:00am I lay in bed too often now panicked by the notion.

Kick back, honey, I tell myself as I stare at the glowing stars I stuck on the bedroom ceiling during the series Heroes when it got too bloody to watch throughout. I should just do what I feel like doing when I get up in the morning and quit pressuring myself to be someone. I already am to my kids, and a few friends. The problem, the war in my head that loops till twilight: ‘Why isn’t that enough for me?’

Close to 30 yrs ago a friend asked me to describe my perfect day a decade forward. From waking up till falling asleep that night, describe in detail what that day looked like to me. Let’s just say I didn’t get close. [Expectations. They’ll screw you every time.] I was supposed to be a known author long ago. I was supposed to have a house in Marin to leave to my well-adjusted, accomplished children. Married to the love of my life. My work read by tens of thousands, my words helping my readers become more personally and socially aware, live better lives.

Did I want too much? I lay in bed wondering why it matters to me that I’ll leave no real imprint on history. Who does, really. Albert Einstein comes to mind. Hitler does too, but oh so very few. And even those names will fade with time, buried under layers of more history.

I want to fall asleep and stay asleep through the night like I used to. I don’t want to be getting up 4 times a night to pee! I’d like to tell you that impending death looming doesn’t feel like the proverbial ax over my head since no one knows when they’ll die, or that age is ‘just a number’ and ‘it only matters how young you feel,’ but that’s all bullshit. You can skydive on your 90th but that doesn’t keep you from being old, and likely rather reckless with fragile bones.

I sigh heavily, then throw the blanket back and roll on my side trying to cool down with my third hot flash of the night. The weight of aging gets harder to bear with each passing year, month, day. Hate to tell ya, there ain’t much upside to getting old. We likely have more life experience, but we aren’t any wiser, most of us stuck in patterns of behavior we adopted in childhood, and the reason history keeps repeating itself.

Look at my phone on the nightstand next to my bed. It’s only 5:10am. I can get up and spend much of the day SMM my latest work to get read and try to ignore the fact that I viscerally hate marketing. Or I can laze the day away writing whatever moves me, reading, baking, building, get a massage, stream Netflix if I feel like it because why the hell not enjoy BEING ALIVE with the limited time I have left…